For decades, the dismantling of ships – also known as shipbreaking – has been carried out under precarious conditions, mainly on beaches in South Asia. These locations account for more than 70% of global shipbreaking, but the activity has taken place with low environmental control and high risks to workers' health.

According to data shared by the NGO Shipbreaking Platform, 409 ocean-going commercial vessels were sold for dismantling in 2024, of which 255 – including oil tankers, bulk carriers, offshore platforms, cargo ships and passenger vessels – were dismantled on the beaches of Bangladesh, India and Pakistan, corresponding to more than 80% of the gross tonnage dismantled globally. These beaches are considered critical points due to the environmental and occupational health risks. Oil spills, contaminated sludge and debris containing heavy metals can cause serious harm to coastal environments and local communities that depend on them .[1].

Give this scenario, the International Maritime Organization (“IMO”) – the United Nations specialized agency responsible for developing international rules related to navigation – initiated in 2005 an international negotiation process to create a specific treaty addressing the end-of-life cycle of vessels. In May 2009, after four years of negotiations among IMO Member States, representatives of the shipbuilding industry and the International Labour Organization (“ILO”), the International Convention for the Safe and Environmentally Sound Recycling of Ships (“Hong Kong Convention”) was adopted in Hong Kong.

The Hong Kong Convention establishes a risk prevention approach at the source, rather than merely mitigate at the end of a vessel’s service life. This means that safety and environmental control obligations begin at the shipbuilding stage and extend throughout its operational life, resulting in controlled recycling. Due to its global and cooperative nature, each signatory party must establish national regulations that ensure equivalent standards of safety and environmental protection.

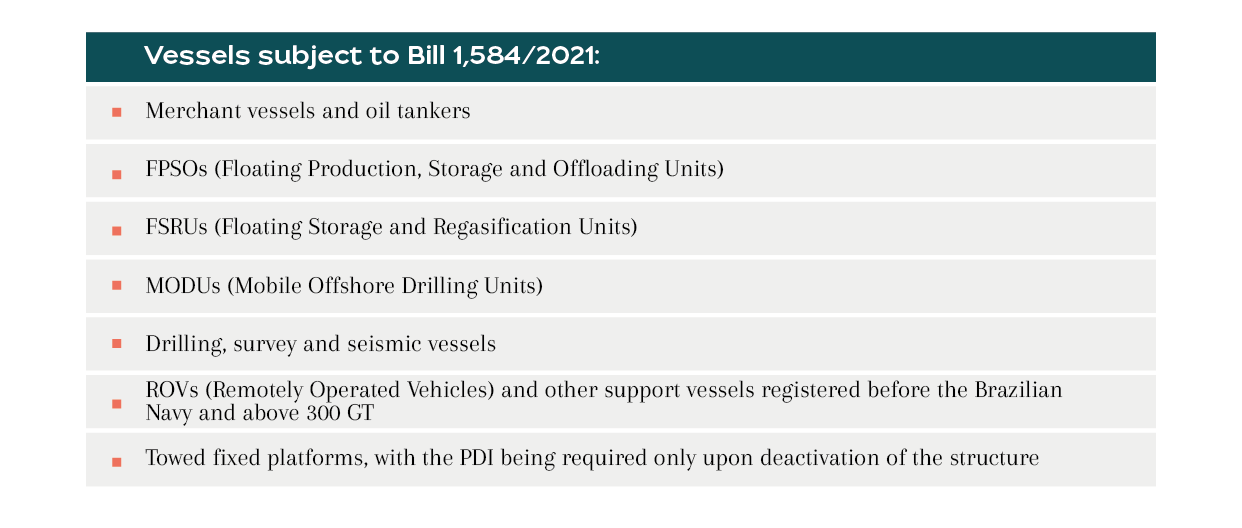

After reaching a minimum ratifications, the Hong Kong Convention finally entered into force for its members on June 26, 2025. Brazil, however, is not yet a party to the Convention – despite having a fleet of over 6,000 vessels under Brazilian Shipping Companies (“EBNs”)[2],[3] and nearly 100 production units, including approximately 68 FPSOs[4]. In this context, Bill No. 1,584/2021 (“Bill 1,584/2021”), currently pending before the National Congress, emerges as an essential regulatory milestone. If approved, it will fill critical regulatory gaps related to the final disposal and recycling of vessels and platforms, aligning Brazil with international best practices.

Bill 1,584/2021: Legislative Procedure

Bill 1,584/2021 – which establishes the national framework for the environmentally sound recycling of vessels and platforms – is pending final assessment in the Chamber of Deputies. The text has already been approved by the Committee on Roads and Transportation (“CVT”) earlier this year, and is currently under revision by the Committee on Constitution, Justice and Citizenship (“CCJC”). It will subsequently be reviewed by the Committees on Environment and Sustainable Development (“CMADS”) and on Foreign Affairs and National Defense (“CREDN”), after which it will be voted on in plenary and submitted for presidential sanction.

Bill 1,584/2021: Context

The Bill proposal emerged in a context of technological renewal and increasing decommissioning in the maritime and offshore sectors. As several oil platforms, FPSOs, FSRUs and support vessels approach deactivation, there is a need for clear rules governing dismantling, final disposal and material reuse, under criteria of safety, occupational health and environmental protection. This scenario becomes even more challenging given the regulatory gap regarding mandatory recycling of vessels and platforms at the end of their service life.

Previously, only the cancellation of registration before the Brazilian Navy was required – a procedure of merely documentary nature.

The National Agency for Petroleum, Natural Gas and Biofuels (“ANP”), through ANP Resolution No. 817/2020, began requiring a Decommissioning Plan (“PDI”). However, the PDI is limited to removal, cleaning and safe abandonment, and does not include the final destination of the hull or material reuse. Currently, the PDI covers only the physical removal of the structure from the sea. With the approval of Bill 1,584/2021, the operator will be required to plan the final destination of the unit in accordance with the environmental guidelines and commitments established under the Hong Kong Convention (even if Brazil has not yet ratified it).

In the absence of a specific regulation, shipowners and operators may freely determine the fate of decommissioned vessels. Many are sold for scrap, exported to Asian countries or kept anchored for years awaiting a decision regarding their final destination. Without legislation requiring decommissioning planning and environmentally sound recycling, these structures often become floating liabilities, accumulating environmental, legal and financial risks.

Ship Recycling Plan and Inventory of Hazardous Materials

If approved, Bill 1,584/2021 will establish national guidelines for the safe and environmentally sound recycling of vessels and platforms. During operation, vessels must maintain an updated Inventory of Hazardous Materials (“IHM”), a technical document identifying and quantifying substances such as asbestos, PCBs (polychlorinated biphenyls), TBT (tributyltin) and other contaminants. The IHM will be mandatory for new builds and existing vessels, constituting a requirement for the subsequent development of the Ship Recycling Plan (“PRE”) and for the issuance of the Ready for Recycling Certificate (“CEPR”) by the Brazilian Navy.

The IHM must be kept updated throughout the vessel’s service life. At each repair, component replacement or structural modification, the operator must review and record changes in the IHM to ensure accurate information on hazardous substances. The Brazilian Navy, as the Maritime Authority, will be responsible for issuing and periodically renewing the Inventory Certificate, which is a document that proofs the conformity of the ship with the Hong Kong Convention

Additionally, Bill 1,584/2021 clearly provides that foreign vessels may be warned, detained, expelled or banned from ports and offshore terminals under Brazilian jurisdiction if they fail to submit a valid Inventory Certificate or CEPR to the Brazilian Navy.

The PRE will become the formal condition for the environmentally sound final disposal of the unit. Accordingly, it will no longer be possible to (i) keep a platform anchored indefinitely without an approved plan; (ii) claim economic infeasibility without defining its lawful destination; or (iii) transfer responsibility to third parties without validation by the Brazilian Institute of Environment and Renewable Natural Resources (“IBAMA”) and the Brazilian Navy. The PRE does not apply during operation but becomes mandatory immediately prior to dismantling and recycling.

Role of IBAMA and the Brazilian Navy

Under Complementary Law No. 140/2011 and Federal Decree No. 8,437/2015, IBAMA holds environmental oversight authority in offshore operations and will therefore be responsible for analyzing and approving the PRE. IBAMA will assess technical and environmental feasibility, establish conditions, monitor implementation, and license and supervise recycling shipyards, in coordination with the Brazilian Navy, which issues the CEPR.

Regarding the IHM, certification will be carried out by the Brazilian Navy, through the Directorate of Ports and Coasts (“DPC”). At the end of a vessel’s service life, IBAMA will act in a complementary role, validating the inventory within the environmental licensing and PRE approval procedures.

Changes in Offshore Planning

According to Bill 1,584/2021, environmental licensing for offshore exploration and production remains unchanged. However, when decommissioning platforms and vessels, the PRE must be submitted to IBAMA. Thus, IBAMA will continue to act as the environmental licensing authority; the Brazilian Navy will serve as the technical certification authority; and ANP will coordinate the decommissioning process.

Note that the Article 4 of the Bill 1,584/2021 covers seismic vessels, FPSOs, FSRUs and towed fixed platforms[5]. All of these units have a high investment value, require significant maintenance and operating costs, and involve large structures and high technical complexity.

The activities associated with these vessels and platforms involve the presence of potentially toxic substances, used in painting, insulation, sealing, lubrication, preservation processes, and, mainly, in the storage and processing of petroleum, natural gas, fuels, lubricants, and industrial chemicals used in offshore operations.

The Solid Waste Management Plan (“PGRS”) already provides for waste disposal during operation. However, the new framework will bring an important advance: all hazardous materials – whether the paint applied to the hull, the oil used in gears, the insulation materials, the oily waste from tanks, or the chemicals used in oil and gas production and separation processes – must be identified, registered, and monitored through the IHM.

The inventory becomes the central instrument for the environmental traceability of the vessel, ensuring that, throughout its entire lifespan – from operation to decommissioning – it is possible to identify, control, and track the presence of harmful substances, including operational and cargo residues stored in tanks, lines, and process systems.

The PRE is a broader and more detailed document based on the IHM and prepared at the end of the vessel’s service life. It will not be limited to the control of hazardous substances, but will encompass the entire physical and functional structure of the unit, defining how each part will be dismantled, segregated, cleaned, treated and disposed of — from the metal hull to electrical cables, pipelines, storage tanks, accommodation modules and internal systems.

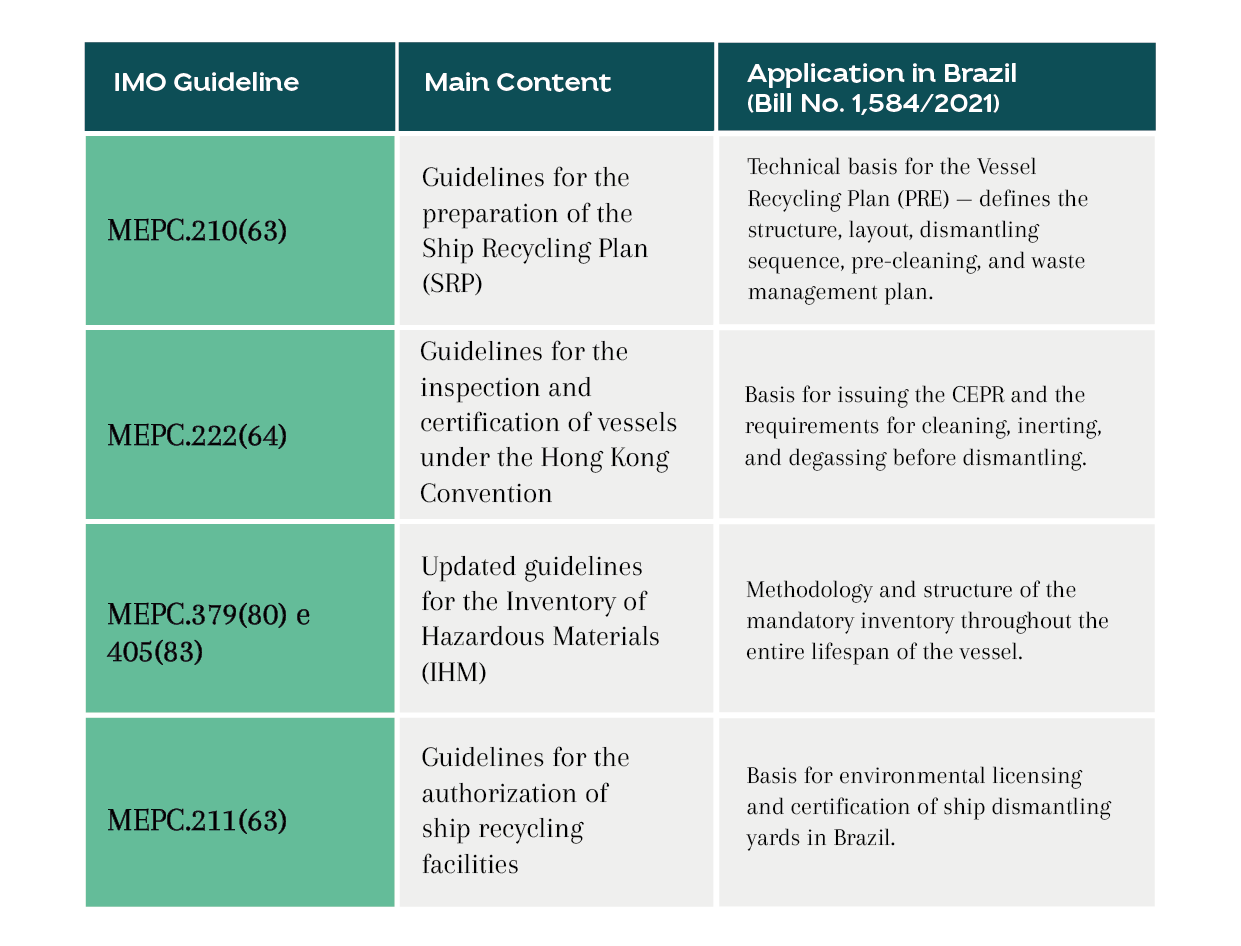

Although Bill 1,584/2021 does not explicitly mention each IMO Marine Environment Protection Committee (“MEPC”) resolution, it mandates compliance with IMO guidelines as minimum technical standards. This means that the procedures stipulated in resolutions MEPC.210(63) (structure of the recycling plan) and MEPC.222(64) (inspection, cleaning and prior inerting) become binding references for IBAMA and the Brazilian Navy in the approval of the PRE and the issuance of the CEPR.

In this way, the PRE must also indicate the procedures for cleaning and inerting the tanks and process lines, ensuring that no oil, gas, or chemical residue remains on board before the start of decommissioning activities. Thus, the new framework seeks to consolidate a model of complete traceability of the vessels' life cycle, extending from preventive identification in the IHM to the safe and certified execution of the PRE, integrating the stages of operation, decommissioning, and final disposal.

Based on this information, it will be possible to ensure that before decommissioning the unit is completely decontaminated, with the removal of oils, compressed gases, sludge, and other remaining products – an indispensable condition for environmentally sound and safe recycling.

New costs and planning for E&P activities

Despite significant environmental progress, oil and gas operations will face increased costs that must be considered in activity planning. Brazil holds the world record for deepwater operations[6], encompassing a wide range of depths, which requires the continuous development of technology and human resources training for the decommissioning of structures.

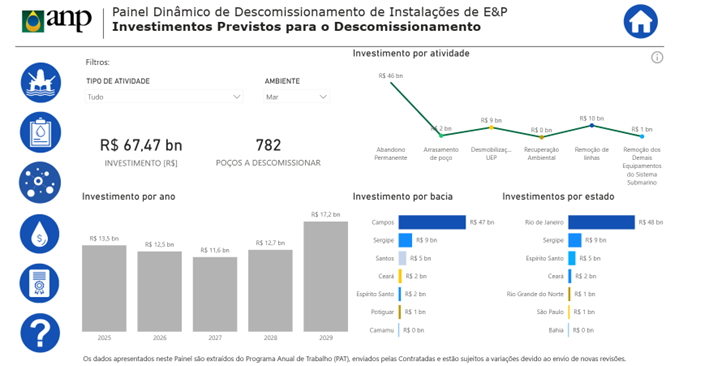

In recent years, several production units have been deactivated and subjected to decommissioning processes. Recent studies indicate that the estimated costs of these activities have increased substantially. ANP forecasts a total of BRL 67.47 billion in investments for the decommissioning of 782 offshore wells between 2025 and 2029 in Brazil.[7].

ANP Dynamic Panel - Decommissioning of Exploration and Production Facilities

With Bill 1,584/2021, in addition to the technical requirements related to dismantling and recycling, the materials resulting from these operations – metallic, electrical, chemical, and structural – must be transported, treated, and disposed of in a traceable manner.

Anticipating the financial impact of this new model, Bill 1,584/2021 also provides for the adoption of economic instruments and support measures, including financing lines, development policies, and the granting of credit incentives aimed at meeting the guidelines of the law[8]. These mechanisms aim to enable the regulatory and operational transition of the sector, stimulating investments in certified recycling infrastructure, decontamination technologies, and safe waste transport, in addition to promoting green reindustrialization through the reuse of materials from dismantled vessels.

[1] Available at https://www.theguardian.com/global-development/2021/mar/11/bangladesh-shipbreakers-win-right-to-sue-uk-owners-in-landmark-ruling and https://www.offthebeach.org/.

[2] Available at https://www.gov.br/antaq/pt-br/noticias/2023/numero-de-ebns-e-instalacoes-portuarias-outorgadas-cresce-em-2022.

[3] EBNs are companies authorized by the National Waterway Transport Agency – ANTAQ to operate in maritime support, port support, cabotage, long-distance, and inland navigation. We note that certain operations do not require the participation of an EBN, as they fall outside the scope of ANTAQ's regulation. This is the case, for example, with the operation of FPSOs.

[4] Available at https://www.bnamericas.com/en/features/snapshot-brazils-floating-production-storage-and-offloading-units and https://cbie.com.br/quantas-plataformas-de-petroleo-temos-no-brasil/.

[5] Article 4 Omitted

V – vessel: any structure, including floating platforms and, when towed, fixed platforms, subject to registration with the maritime authority and capable of moving on water, by its own means or not, transporting people or cargo;

[6] Available at https://www.woodmac.com/news/opinion/global-deepwater-production-to-increase-60/.

[7] Available at https://app.powerbi.com/view?r=eyJrIjoiZjFlMWI0MDgtNWNiNC00OTZlLWI3NGQtOGM3MjQwODhjMTMwIiwidCI6IjQ0OTlmNGZmLTI0YTYtNGI0Mi1iN2VmLTEyNGFmY2FkYzkxMyJ9.

[8] Article 18. In promoting or granting credit incentives intended to meet the guidelines of this Law, official credit institutions may establish differentiated criteria for beneficiaries' access to credit from the National Financial System for productive investments.

Article 19. The Union, the States, the Federal District, and the Municipalities, within the scope of their competencies, may establish rules with the objective of granting tax, financial, or credit incentives, respecting the limitations of Complementary Law No. 101, of May 4, 2000, to: [...]